‘Hi Bruno, would you like to do a rock climbing course with us?’

‘Yeah, I would like that.’

The introductory course with the Victorian Climbing Club immediately fired up my passion. Being athletically built, ex-sprinter, skilled in gymnastics and a natural risk taker, I quickly progressed to the more difficult climbs. A determined newcomer usually attracts the attention of the establishment, so I was picked to climb with Chris Dewhirst. He was one of the elite ‘hardmen’. Chris was a tall, wiry Englishman, very intelligent and with a sharp wit. He sometimes beat me at chess, and on the rock face he was the master and I, aged twenty seven, was the apprentice. He laughed a lot and had a-nothing-is-impossible attitude. Thirty years later, he successfully flew two balloons over Mount Everest.

Having done several hard climbs with Chris in the following months, we attempted ‘Blimp’. It is a rock climb in the middle of a cliff named Bundaleer in the Central Grampians in Victoria.

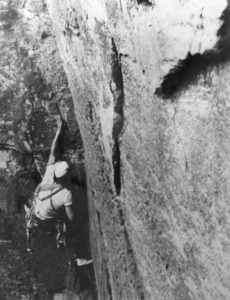

The cliff is overpowering, steep and with massive overhangs. In 1968 Blimp was the great unsolved climbing problem in Victoria, having defeated several strong attempts. It was named and made famous by the legendary Peter Jackson, who was regarded as the father of Australian rock climbing. The climb followed a long, finger-thin crack in a steep corner, between two smooth and overhanging rock faces. The exit at the top was blocked by a two-metre flat ceiling.

Chris tried very hard all weekend, but he always got stuck at the crux point about a third of the way up. If Chris could not do it, I certainly gave it no further thought, so we packed up and went home.

In January of 1969, I had an invitation to have another go at it, this time with John Ewbank from Sydney. He was the leading climber in Australia, and I regarded him with great admiration. Jackson told him about Blimp, and Ewbank asked me to climb with him. I was so excited, that it did not even occur to me to ask Chris for permission to do the climb without him. John Ewbank arrived in Melbourne with his girlfriend Valerie, who taught clarinet at the Sydney Music Conservatorium. And so along with Fred Langenhorst and Rein Kamar (both RMIT climbers), we all packed the gear into my car and headed for the Grampians. That Friday night around the campfire, Valerie and John played on their guitars, and she sang sad songs. Then John turned to me.

‘So you’ve already had a go at Blimp?’

‘Actually, no I haven’t. I spent all weekend standing on the ground, holding the ropes for Chris, who had several goes at it.’

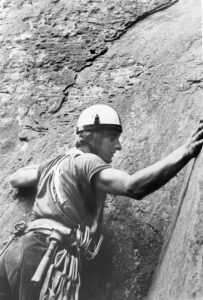

On Saturday morning we arrived at the bottom of the climb, and everyone got busy. Valerie took off her T-shirt and stretched out on a nearby rock to work on her suntan. Fred and Rein climbed up a line of bolts, previously banged into the smooth rock face to the right of Blimp, for the express purpose of filming its first ascent. They alternately used my battered Minolta camera to get a different viewpoint. John stood at the bottom of the climb and quietly studied it, while I busied myself with fixing the ropes to anchor myself to a nearby tree, just like I did for Chris. If the lead climber fell, I would hold the rope and arrest his fall. His health and possibly his life depended and how well I did that. The cliff was in the shade and the air smelled of rotten eucalyptus leaves. I loved it.

John had extremely blue eyes and long curly blond hair. He wore a red jumper and short golf-like climbing pants, with long red greasy wool Norwegian socks, which was the fashion of the day. A climbing helmet, equipment belt with lots of gear hanging of it, and climbing boots with smooth soles completed the outfit. We all dressed in a similar way. John oozed confidence and was eager to get going. I was quietly apprehensive that he may actually get up, and I would have to follow him. Rein and Fred were hanging from bolts high up on the face with my camera, ready for action. The scene was set. Eventually, all was ready and before John made the first move Valerie said, ‘You know a girl could get pregnant just being near you, with so much testosterone and adrenaline in the air.’ We all laughed and it eased the tension somewhat. I thought that John would show us how to do it and that we will have it on film. But aloud I said, ‘I like your red socks’.

John moved up the rock with the grace of a ballet dancer and a cat, in short deliberate moves punctuated by a concentrated study of the next move. He placed protecting gear, such as pitons and crackers into the climbing crack and moved up again. He easily passed the first three of the difficult spots. Then John moved up to the point where Chris and everyone else before him reached and said, ‘Wow! I can see what Jackson was talking about’.

He studied it for a while, then came down and rested. John had several attempts but didn’t commit to the hard bit. We went back to the campsite for the night.

‘So Fred did you get some good pictures?’, said Valerie once we settled in. John cut the answer short. ‘What good would they be if we don’t make it up?’

We slept little that night. I thought, surely John will solve Blimp’s riddle made up of all those

strenuous and risky chess moves. On Sunday, John climbed up and down, always reaching the same point, and by three o’clock in the afternoon he came down and said, ‘It’ll have to wait till another time’.

At this point I felt a huge energy rush, and a determination swelling in me. Without knowing what I would do, I started putting my climbing boots on.

‘I wanna have a go John’, I said. Fred and Rein looked at each other puzzled and stayed up on their bolt line.

‘Yeah, you may as well, since everyone else has’, said John.

So we swapped roles and I started off. I remembered all the moves by heart, that Chris and John had made, and climbed quickly, preserving energy. When I reached the high point John got up to, I instantly understood why it had all ended here for everyone else. Above me was an overhanging thin crack in crumbly rock with enough space to push fingertips just half way in. That was all. There were no other handholds, nor footholds, and no place to put protection of any sort. I went on and on. This required total commitment and sustained strength. The long crack led to an overhang where I could probably place protection. But it was a long way off.

Rein yelled out. ‘Hi Bruno give us a smile for the camera and go for it.’ So I turned around, smiled and committed myself. The adrenalin rush helped. Every two metres I had to stop and hang on one arm to rest the other. There was no support for the feet. I moved slowly, painfully, grunting a lot, and so focused on each next move that I was not even aware of the risk I was taking. If I fell off now I would hit the ground and be crippled for life. I was further above the last protection than it was from the ground level. My one thought was to reach the base of the roof above and secure myself. My weight training and gymnastics paid off here. I felt I could sustain the effort for a while. I heard no other noise except my own heart, heavy breathing and Beethoven’s Fifth symphony, the music thundering in my ears. The stress got unbearable, beyond fear, and beyond pain I could still register. My body numbed, but the fingers held on and that was all that mattered. Nothing mattered as long as I held on. Voices in my head started arguing with each other.

‘Go on fall off, you won’t have to struggle any more.’

‘Ta da, da dah’, thundered Beethoven.

‘Don’t listen to them, just rest up your hand and move up, again and again.’

Eventually, I could stop and get a small purchase on one foot to take most of my weight off my arms. It was enough. I breathed heavily and I knew I would be alright for a while. A few more minutes and I reached the roof and rested. It was uncomfortable there. If I stood up my head had to be bent to the side or I have to hang on my arms again. I bent my head and banged in a solid piton into a crack and secured a rope trough it. I was safe now. My confidence returned. I surveyed the overhang. That was the next problem. The exit was to the left along a mossy ledge extending for almost two metres. There were holds for the fingers and absolutely nothing for the feet. The ledge started off several centimeters wide, sloping down and gradually narrowed to nothing at the end of the overhang. Having rested I regained my humour and yelled down, ‘This is really tricky, so hang on tight on the ropes’. I cleaned the ledge with my fingers, throwing lots of rubbish in John’s face below, and on the third attempt I reached the exit point. Time was running out, my energy nearly spent, and if I didn’t commit to the overhang now I would simply fall off from exhaustion. So with a loud ‘Urgh!’, I put my left hand on the only hold available and pulled up. The rest happened very fast. The feeling of exposure gave me such a boost, that I swung over the overhang and I was up.

I could not believe it. I had just done the first ascent of Blimp. Following lots of jubilant screaming from below, I secured myself to a tree at the top and yelled down, ‘Climb when ready.’ John climbed up, grunting and muttering mild obscenities in admiration, but with the confidence of the top-rope from his waist to my hands. Eventually, he came up offered his hand and said, ‘Welcome to the world class mate’. Strangely I felt humbled by the experience. I came very close to my limit on this climb.

Back in Melbourne John Ewbank got on the phone and told Chris Baxter and Peter Jackson about the climb. My life had changed. I acquired a ‘persona’ which did not agree with the usual image I had of myself as a person who was withdrawn somewhat.

Thank you Glen for publishing the story and arranging the images.,

The story about the 1st ascent of Blimp was not written for the rock climbing magazine or even their audience.

Rather it was a human drama about the power of will and a somewhat suicidal attempt by a young and up-coming climber.

It was written for the Melbourne Writers Group as one of the regular 1500 word stories for review by the group.

This is why it was written in such colourful language.

The Blimp climb was named by Peter Jackson who documented the various possible climbs on the cliff. It was named after a British comic character named Colonel Blimp. see- https://www.criterion.com/films/359-the-life-and-death-of-colonel-blimp

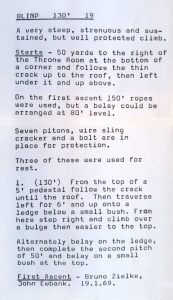

To answer your question now; I did a rock climbing course in March the previous year and did Blimp in January the following year, so i had about 10 months of experience. I don’t recall putting in 7 pitons. I eliminated the initial aid lower down, then there was a bolt before the crux and then a piton under the overhang. I don’t think I would have had the time or strength to put any other pitons in. You may need to refer to the original write up in the Argus. The description you included with the climb is different to mine, no doubt to suit today’s style.

see above

FANTASTIC CLIMB

FANTASTIC READ

Never read a better Aus climbing story… thanks